Meliponiculture in agroforestry systems in Belterra, Pará, Brazil

Meliponicultura em sistemas agroflorestais em Belterra, Pará

Meliponicultura en sistemas agroforestales en Belterra, Pará, Brasil

Ana

Paula da Silva Viana1, Daniela Pauletto![]() 2,

João Ricardo Vasconcellos Gama3, Adcléia

Pereira Pires4, Hierro Hassler

Freitas Azevedo5, Aline Pacheco6

2,

João Ricardo Vasconcellos Gama3, Adcléia

Pereira Pires4, Hierro Hassler

Freitas Azevedo5, Aline Pacheco6

1Engenheira

Florestal, Estagiária Voluntária no Instituto Chico Mendes de Conservação da

Biodiversidade, Santarém, Pará, anastm.paula@gmail.com; 2Mestre

em Ciências de Florestas Tropicas e Professora no Instituto de Biodiversidade e

Florestas, Universidade Federal do Oeste do Pará, Santarém, Pará, daniela.pauletto@ufopa.edu.br; 3Doutor

em Ciência Florestal e Professor no Instituto de Biodiversidade e Florestas,

Universidade Federal do Oeste do Pará, Santarém, Pará, jrvgama@gmail.com; 4

Mestranda

em Ciências Ambientais, Universidade Federal do Oeste do Pará, piresadcleia@gmail.com; 5Bacharel em produção animal, Instituto

de Biodiversidade e Florestas, Universidade Federal do Oeste do Pará, Santarém,

Pará, hierroazvdo@gmail.com, 6Doutora em Ciência

Animal e Professora no Instituto de Biodiversidade e Florestas, Universidade

Federal do Oeste do Pará, Santarém, Pará, alinepacheco@outlook.com

Recebido: 01/05/2020;

Aprovado: 23/11/2020; Publicado: 10/02/2021

Resumo: O objetivo do estudo

foi caracterizar a produção meliponícola em sistemas

agroflorestais e realizar um levantamento de espécies vegetais indicadas pela

visitação por abelhas sem ferrão no município de Belterra,

Pará. A pesquisa foi realizada a partir de um questionário aplicado a meliponicultores

com questões que abordaram aspectos socioeconômicos e da produção de abelhas

sem ferrão. Em relação ao pasto meliponícola foram

investigadas as espécies vegetais apontadas como visitadas pelas abelhas. Destaca-se que 15% dos criadores tem como

principal atividade econômica a meliponicultura e 54%

vivem com 1 ou 2 salários mínimos. O tempo na

atividade de meliponicultura apresenta amplitude de 2

a mais de 40 anos. Os entrevistados afirmaram se dedicarem à meliponicultura pela afinidade com a atividade e pela

consciência na importância das abelhas para o meio ambiente. Os

meliponicultores apontaram que os maiores entraves enfrentados estão

relacionados ao desmatamento e ao uso de agrotóxicos o que, segundo os mesmos, implica na redução na produção do mel, principal

produto comercializado. Observou-se que os sistemas agroflorestais (SAFs) onde estão inseridos os meliponários

apresentam, segundo os entrevistados, 38 espécies florestais distribuídas em 21

famílias botânicas. Predominaram as

espécies frutíferas, características de floresta primária e secundária, o que

poderá indicar potencial para introdução em quintais agroflorestais ou outros

sistemas consorciados minimizando os custos de implantação e manutenção de meliponários.

Palavras-chave: Quintais agroflorestais; Pasto meliponícola;

Agricultura urbana.

Abstract: In this study we characterized

the honey production in agroforestry systems and inventing the

species visited by stingless bees in the region of Belterra, Pará. We used a

questionnaire applied to honey producers with questions that addressed socioeconomic

conditions and the production of stingless bees, as well the plant species visited

by bees. Fifteen percent of bee breeders have meliponiculture

as their main economic activity and 54% live of 1 or 2 minimum wages. The time

in meliponiculture activity ranges from 2 to over 40

years. According to the interviewees, they dedicate themselves to meliponiculture due to their affinity with the activity and

their awareness of the environmental importance of the bees. The greatest

obstacles cited was the deforestation and the use of pesticides, which,

according to them, implies a reduction in the production of honey, the main

product sold. The agroforestry systems (SAFs) where the meliponaries

are inserted present, according to the interviewees, 38 forest species

distributed in 21 botanical families. Fruit species predominated,

characteristics of primary and secondary forest, indicating potential for

introduction into agroforestry yards or other intercropped systems, minimizing

the costs of implanting and maintaining meliponaries.

Key-words: Agroforestry yards, Meliponic

pasture; Urban agriculture.

Resumen: El

objetivo del estudio fue caracterizar la producción de miel en sistemas agroforestales y

realizar un relevamiento de

especies vegetales

indicadas por visitación de abejas

sin aguijón en el municipio

de Belterra, Pará. La investigación

se realizó a partir de un cuestionario aplicado a productores

de miel con preguntas que abordaban aspectos condiciones socioeconómicas y producción de abejas sin aguijón. En

cuanto al pasto melipónico,

se investigaron las especies vegetales identificadas

como visitadas por las abejas.

Es de destacar que el 15% de los

ganaderos tienen la meliponicultura como su principal

actividad económica y el

54% vive con 1 o 2 salarios

mínimos. El tiempo en la actividad meliponicultural

varía de 2 a más de 40 años.

Los entrevistados manifestaron que se dedican a la meliponicultura

por su afinidad con la actividad

y su conciencia de la importancia de las abejas para el medio ambiente. Los

meliponicultores señalaron que los

mayores obstáculos que enfrentan

están relacionados con la deforestación y el uso de pesticidas, lo que, según ellos, implica una reducción en la

producción de miel,

principal producto vendido. Se observó

que los sistemas agroforestales

(SAF) donde se insertan los

meliponarios presentan, según los entrevistados, 38 especies forestales distribuidas en 21 familias botánicas. Predominaron las especies frutales,

características de bosque primario y secundario, lo que puede indicar potencial de introducción

en patios agroforestales u otros sistemas

intercalados, minimizando los costos

de implantación y mantenimiento

de meliponarios.

Palavras claves:

Patios agroforestales; Pastos

melipónicos; Agricultura urbana.

INTRODUCTION

The western of Pará

has undergone changes in landscapes with the expansion of the agricultural

sector, mainly linked to the paving of the Cuiabá-Santarém

Federal Highway (BR - 163), one of the main frontiers for the expansion of agribusiness.

In the region, as well as in a considerable portion of the Amazonian territory,

there was a reduction or suppression of forests, generating the occurrence of

mosaics. The mosaics are based on a defined previous itinerary, followed by

forest exploitation with clear cutting, burning, and implantation of pastures

for breeding animals for slaughter, as well as the spread of mechanical crops

such as soybeans (LOUREIRO; PINTO, 2005; SILVA et

al., 2016).

In the area of Belterra, the production system

of high technological level provided the rapid growth of production based on

monoculture plantations such as rice, corn and

soybeans, which negatively affected the landscape of the region, and caused the

forest fragmentation (VENTURIERI et al., 2007). In 2010, 6.2% (27,274 ha of

planted area) of Belterra territory was occupied by crops, especially

monocultures, such as rice, soybeans and corn (DEEPAST, 2020).

The unrestrained

expansion is impacting family production systems and has been an obstacle for extractivists and small animal producers, such as bee, that

are susceptible to forest fragmentation and intensive use of pesticides (RAYOL;

MAIA, 2013). Among the species susceptible to these kind of

disturbances, the bees of the Meliponini tribe

can nest and forage in anthropized environments, however, they prefer

environments with greater plant diversity, availability and diversification of

food, being Meliponini tribe more diverse in these

environments (WINFREE et al., 2009). In these environments there is a

mutualistic relationship, through pollination (collection of nectar and pollen;

cross-fertilization) that benefits both bees and plants. Bees and vegetables

are intrinsically linked, that is, the loss of pollinating bee species, can

lead to the plant species extinction (SANTOS, 2010).

The availability of

nesting sites also contribute to maintaining the

diversity of bees in areas subjected to human pressure (SILVA et al., 2012). Therefore,

the knowledge of the species used as meliponic

pasture, plant species that provide nectar and pollen for the maintenance of

the colony and production of honey and other derivatives (SILVA; PAZ, 2012), is

essential for conservation actions and production of honey and other

by-products and services.

Characterizing meliponiculture exercised by breeders in the region of

Belterra and provide information is important to support the creation of

consortium systems that provide foraging, meliponiculture

and multiple use, providing resources for bees with low cost of implantation

for producers, also contributing with conservation strategies. Therefore, the

present study aimed to characterize honey production in agroforestry systems by

conducting a survey of plant species visited by stingless bees in the

municipality of Belterra, Pará.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

The study was carried

out in the area of Belterra, state of Pará, Brazil, in

13 agroforestry systems. The systems consisted of urban and peri-urban

perimeter, that is, the surroundings of the urban area with a predominance of

agricultural activities by the residents. We applied semi-structured questionnaires

to 13 meliponicultors, owners of the meliponiculture. Ten are located in

agroforestry yards, in the urban perimeter, and three in other agroforestry

systems located in areas of family farming production, at a distance of at

least 5 km from the residence, and adjacent to native forest areas.

As a criterion for

data collection, we identified and interviewed the producers that remain

exercising the activity of meliponiculture, by handling

and extracting the honey or other products and that worked in the central area

of the municipality or in the urban perimeter margins.

We adopted the snowball methodology (BAILEY, 1994),

sampling from January 2017 to January 2018. The questionnaire covered questions

about socio-economic profile of honey farmers, survey of honey pasture by the

indication of species visited by stingless bee species (SBS) and beekeeping

productivity data of SBS (years 2016 and 2017). The challenges and objectives

of creating SBS, the technical assistance received and training in the area of meliponiculture

were also investigated.

In the section on meliponic pasture, the interviewees pointed out, from

personal observations, the popular names of the plant species visited by the

SBS. The identification of these species was carried out with the support of

technicians from the Federal University of the West of Pará with para-botanical

knowledge and extensive experience in botanical identification. Subsequently, we

carried out a bibliographic survey of the scientific names of the species, as

well as their botanical families and use.

Meliponicultors had previously information

about the scientific names of SBS, which were identified by researchers from Embrapa. All interviews read a consent form for the

research and signed it. For data analysis, we used descriptive statistics for

the quantitative and qualitative interpretation of the results, and

identification of central tendency measures.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Among the main

economic activities of SBS breeders in the municipality of Belterra - PA, are

agriculture (23%) and freelancers (23%) (Figure 1). For 15% of the meliponiculturists in Belterra, meliponiculture

is the main economic activity, also verified by Pinto (2012) in a study of the

profile of meliponiculturists in Belterra in 2010. Meliponiculture is a complementary activity in many regions

of Brazil, and agriculture is in most of the time, the main source of income

for honey farmers (MAGALHÃES; VENTURIERI, 2010).

Figure 1. Main sources of income of stingless bee producers in

the municipality of Belterra, Pará.

Most meliponicultors (69%) are over 50 years old (Table 1),

which corroborates Pinto (2012) and Siqueira (2014) who also found that most meliponiculturists are over 50 years old. We also found

that the meliponicultors have been engaged in the

activity for more than 10 years (38%), 38% exercise the activity for less

than ten years, 8% are in the activity for over 20 years, and two of the

largest meliponicultors in numbers of colonies (15%),

have been carrying out the activity for more than 40 years. Meliponiculture

is a traditional activity in the study region, carried out a long time ago, by

the original peoples (RAYOL; MAIA, 2013), which may explain the execution of

the activity for more than 40 years by 15% of the interviewees.

Most of the meliponiculturists in Belterra have only elementary (15%)

or high school (46%) and 8% higher education. Regarding the monthly family

income, 54% receive from 1 to 2 minimum wages, those who receive more than 5

minimum wages (23%) are retired civil servants and traders (Table 1).

|

Table 1. Socioeconomic profile of stingless bee producers in Belterra, Pará. |

||

|

Variable |

Total respondents |

|

|

N. |

% |

|

|

Age range |

||

|

from 30 to 39 years |

2 |

15 |

|

from 40 to 49 years |

2 |

15 |

|

More

than 50 years |

9 |

69 |

|

Scholarship |

||

|

High

school |

6 |

46 |

|

Incomplete elementary school |

4 |

31 |

|

Complete

elementary school |

2 |

15 |

|

Higher education |

1 |

8 |

|

Family income |

||

|

Less than 1 wage |

1 |

8 |

|

1

to 2 wages |

7 |

54 |

|

2

to 3 wages |

1 |

8 |

|

3

to 5 wages |

1 |

8 |

|

More

than 5 wages |

3 |

23 |

|

Gender |

||

|

Male |

13 |

100% |

Meliponicultors generally inspect

the colonies once a week, but some said they were engaged in the activity

daily. Pereira et al. (2010) recommend the review of colonies at least every 30

days to check if they are moldy, with the presence of offspring and queen,

availability of food, presence of natural enemies and garbage that are

indicators of colony health.

Costa et al., (2012),

studying meliponiculture practiced in traditional

communities of Parintins/AM, observed that the

breeders who inspected the colonies at least once a week had stronger and more

vigorous colonies than those whose inspection was rare, which they were weak or

abandoned their nests.

The creation of SBS

generally occurs in line with other activities for 38.5% of the population,

such as poultry (80%) or other small animals (20%). Barth (2004) and Costa et

al., (2012) affirm that bees can collect material of fecal origin and,

therefore, the proximity of the meliponaries to the

breeding of small animals, such as poultry and pigs, is not recommended as contamination

of the produced honey.

In 69.2% of the

properties there is occurrence of native forest in the vicinity of the meliponary, within a radius of approximately 3 km, a

determining factor for honey production. According to Silva and Paz (2012),

each bee species has a different flight capacity (600 to 2,400 meters) varying

according to body size. Although there is native forest in the vicinity of the

studied meliponaries, the size of the vegetated areas

was not specified here.

According to the producers, 76.9% learned how

to manage bees without technical assistance, however, 54% of them participated

in courses on SBS creation offered at different events or they looked for

courses by themselves.

The majority of respondents (42%)

pointed out that they create SBS to obtain products for sale. However, 29%

stated that they exercise the activity only as hooby

and for 29% the creation of bees aims to obtain honey for their own

consumption. In addition, 46% of meliponicultors sell

honey, which is the main product sold. When asked about the sale of other

products, 43% stated that they sell “samburá”, “cerumen”

(29%) and “propolis” (28%).

Honey was the first

SBS product to be explored by man due to its nutritional and medicinal value,

which is why the product is still valued by many populations today

(CORTOPASSI-LAURINO et al., 2006; MELO et al, 2010). Gehrke

(2010) observed that those producers who practice meliponiculture

as a hobby are apt to be effective meliponicultors.

Regarding the

breeding stock, 82% of the breeders multiply their colonies to increase

production. Of these, 62% sell

the new colonies to other producers.

The price of honey is

different for species that have recognized medicinal value by the population.

In the case of the jataí species (Tetragonisca sp.), whose honey is

indicated for the treatment of cataracts, its value reaches R$ 200.00 kg-1. SBS honey has anti-inflammatory and healing

properties attributed to the habit of collecting resins with medicinal

properties. SBS honey also has a different characteristic from that of Apis melifera,

with no sucrose in its composition (SANTOS, 2010; LIMA and NOGUEIRA, 2017).

However, scientific studies with SBS are still very incipient when compared to

studies related to Apis melifera, as

well as the lack of development of appropriate technologies (SILVA and PAZ,

2012; SANTO et al., 2016).

The main problems

faced by SBS producers were deforestation, reported by 42% of respondents, and

the use of pesticides in the surrounding crops, for 34% of meliponicultors.

The impacts of deforestation were studied by Brown and Oliveira (2014) who

found in recent studies in the Amazon, a significant relationship between

deforestation and the reduction in the richness of stingless bee species,

revealing the important to discuss the advances of agribusiness in the region

and their impacts on economic activities traditionally performed by the peoples

of Belterra.

Freitas and Pinheiro

(2010) report that the attractiveness of flowering poisoned by pesticides is

the main reason for the death of pollinators (lethal effect). However, even low

doses, lower frequencies of use and even flowers affected by the pesticide

drift effect, that is, flowers close to the areas of application contaminated by

air, can cause side effects reducing the vigor of the colony. According to the

authors, in large areas of crops such as soybeans and corn, with a single

application of a large amount of pesticides, the

impact on bees may be more severe, because of the huge amount of poison

released into the environment in a short time.

Meliponiculturists

interviewed also cited as challenges the influence of seasonality in production

(8%), since flower production is also conditioned by seasonal conditions, and

the lack of technical training, pointed out by 4% of producers. All interviewed

breeders claim not to receive continuous and permanent technical assistance

from government agencies or private institutions, do not market their products

with labels and do not have organic certification.

The

incipient legislation was reported by 8% of the interviewees as another

bottleneck for the consolidation of the activity, while the low availability of

places with meliponic pasture that offer security for

the installation of colonies was cited 4% of the meliponicultors.

The frequent thefts of colonies reported by the interviewees makes impossible

to install the meliponaries in remote areas. The

CONAMA resolution No. 346, of June 6, 2004, provides guidelines for the

implementation of the activity, although it is necessary laws that regulate the

activity at the state level considering regional characteristics.

Barth (2004) pointed

out the advance of deforestation, use of pesticides, vandalism in rational

creations as challenges to be overcome by meliponiculture.

The author also cited as a limiting factor the lack of standardization in

production, linked to the limitation in specific legislation for the sector.

These obstacles generate discrepancies in the form of collection and packaging

of SBS products leading to greater or lesser care, contamination

or alteration of the quality of the product and, consequently, loss of

credibility in the market.

Agroforestry yards

are suitable spaces for the creation of ASF for the safety of the colonies and

the possibility of developing the activity together with the family. These

spaces form true refuges for pollinators, mainly bees, and the creation of

these in agroforestry yards provides important sources of foraging,

contributing to the preservation of these species (FERNANDES et al., 2009;

IMPERATRIZ-FONSECA et al., 2012).

The producers

revealed that despite the difficulties encountered in the creation, they are

very fond of the activity and do not intend to abandon it. Another determining

factor for maintaining the activity for so long is the ecological awareness

that the interviewees have, since they all cited the importance of bees for the

maintenance of the forest and of the man himself. This conservationist attitude

of the breeders was also observed by another study (MEIRELES et al., 2018).

Most producers are

owners of the site (84.6%) and 15.4% maintain the beekeeping in partnership

with other meliponicultors because they do not have

enough pasture on their properties or do not have enough time to inspect the

SBS colonies.

We found eight species

of stingless bees present in the meliponaries, the

most frequent being Jataí, occurring in 10 yards and

totaling 49 colonies (Table 2). However, the largest population found was Scaptotrigrona sp.

with 814 colonies in 8 yards. Species of this genus generally have a good honey

production and are easy to handle due to their low defensive behavior (COSTA et

al., 2012).

|

Table 2. Species, occurrence and number

and percentage of colonies counted of stingless bee breeding in the urban

area of Belterra, Pará. |

||||

|

Popular

name |

Cientific

name |

Occurence* |

Nº

Colonies |

%

Colonies |

|

“Jataí” |

Tetragonisca

angustula |

10 |

49 |

5,0 |

|

“Canudo” |

Scaptotrigona

aff. xanthotricha |

8 |

814 |

83,4 |

|

“Jandaíra” |

Melipona

interrupta |

6 |

18 |

1,8 |

|

“Cacho de uva” |

Frieseomelitta

longipes |

6 |

36 |

3,7 |

|

“Jataí mirim” or “mosquito” |

Plebeia mínima |

5 |

27 |

2,8 |

|

“Uruçu amarela” |

Melipona

flavolineata |

4 |

10 |

1,0 |

|

“Uruçu cinzenta” |

Melipona

sp |

2 |

2 |

0,2 |

|

“Uruçu boca de renda” |

Melipona

semingra |

2 |

20 |

2,0 |

|

*Number of yards in which they

occur |

||||

The products produced

from the species of the genus Melipona are widely used by populations, both in

food and medicinal use and when well

managed, they can have their production optimized for about 1L of

honey/colony/year (COSTA et al., 2012).

The species Melipona seminingra

is considered endemic to the Belterra region, according to the survey carried

out with the producers. It is a subspecies, which in Belterra has an orange

thorax and the first abdominal segment is lighter than the subspecies M. seminigra perningra occurring in the eastern portion of the

Amazon (VETURIERI, 2009).

The species Frieseomelitta longipes,

according to local producers, has great potential due to the different flavor

of honey, although its colony production is inferior to the “canudo” species, considered as the most productive of the

listed species. However, based on the reports from the producers, the “caho de uva” species is

identified as the largest producer of propolis. F. longipes was identified by Cordeiro

and Menezes, (2014) as a good producer of pure resine

propolis.

Species of the genus Scaptotrigona (Canudo), found in

the Belterra region, are largely bred by small farmers in various regions of

the country, who even have meliponaries with more

than 200 boxes and with a record of productivity above 8 liters/box/ year

(LOPES et al., 2005). In the present study, the largest population of “canudo” found corresponded to 300 colonies distributed over

an area of 6,250 m2.

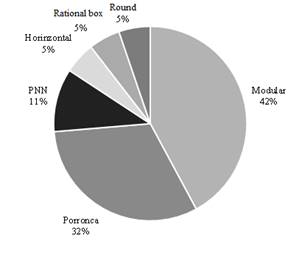

The type of modular box was the most frequent among producers (42%),

followed by the “Porronca” model, with 32% of the

options (Figure 2). There are places where there is more than one box model on

the property, therefore, the quantity presented is related to the number of

yards that have such models and not to the number of boxes installed in

Belterra.

Figure 2. Percentage of option

by type of stingless bee box found in the areas of honey producers in Belterra,

Pará.

As for the structure

of the boxes, the modular one has a nest, over-nest

and beehive (Figure 3A and 3B), which presents advantages in the time of the

multiplication of the swarms as ease of removal of the brood discs, and

separate compartment with the necessary supply for temporary feeding of the new

colony. In addition, this type of box is indicated to improve the development

of the swarm, increase the production of honey and

provide welfare to the bees (LIMA; NOGUEIRA, 2017).

Producers usually

test new models of boxes according to the technical and empirical knowledge

acquired over the years of creation. Among the new models, the round box stands

out (Figure 3C), which is similar to the natural

nesting of bees established in the trunk of trees and is in the experimental

stage of use.

The "porronca" or "cabocla"

(Figure 3D) has a more simplified structure, without compartments, has as the

main advantage the possibility of expanding the nest due to the availability of

space. However, the producers reported that this model presents difficulty at

the time of nest multiplication, since the absence of compartments in the box

structure limits the partial removal of the daughter colony without causing

damage to the remaining colony.

Figure 3. Modular box (A and B) and round box (C) and “Porronca”

(D) models used in Belterra, Pará.

Source: Personal archive,

2017.

The average honey

production per colony/year was 3.0 to 3.1 L ± 0.5. According to Maia-Silva et

al. (2016) the size of the foraging area directly influences the amount of food

sources, on the other hand, botanical varieties are important, as the SBS will

be able to choose according to preference.

The honey collection is carried out in the least rainy period of the

year, just after the end of the blooms. This product is first removed in

containers, then filled in the packaging, usually glass or plastic bottles, and

stored in the refrigerator or at room temperature.

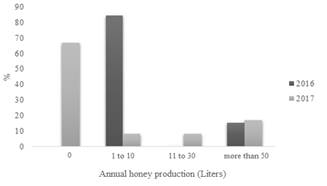

Analyzing the honey

production in 2016, 34% of the producers extracted 60 to 90 L, and 11% of them

extracted 1,000 L in the same period, which may suggest that productivity is

related not only to the number of colonies, but also with the availability of meliponic pasture. However, in 2017, the majority (67%) of

producers were unable to commercialize honey because the colonies did not

produce enough for the harvest and only 17% managed to obtain more than 50 L of

production (Figure 4), and of these 23% reported who lost colonies due to the

death of bees or abandonment of the colony.

Figure 4. Production of honey from stingless bees by meliponary

per year, in the municipality of Belterra, Pará.

Two producers who

owned more than one hundred colonies reported that they were giving up the

activity with a commercial bias and that they would continue with few boxes due

to their affinity with the creation and conservation of these. The reason for

the withdrawal reflects the difficulties faced, as the increase in the

production of these has come up against the lack of meliponic

pasture, since the forest areas in the region are becoming fragmented and the

producers report the death of many swarms.

The analysis of the

dynamics in the landscape in Belterra over 13 years, through analysis of

satellite images by the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI),

concluded that there were significant changes in vegetation, mainly due to the

increase in anthropized areas, which implies in loss of habitat and resources

for various components of fauna, including bees (CORRÊA et al., 2011).

The use of pesticides

in the vicinity of the meliponaries has been cited by

producers as a preponderant to swarm deaths, becoming yet another obstacle in

production, especially in peri-urban areas. In their studies Venturieri (2009) warned that in the medium term, the

exploitation of trees with diameters over 50 cm would affect the density of

stingless bees, causing low reproduction of tree species intrinsically

dependent on these pollinators.

The plant species in

the meliponaries and surroundings, identified by the

producers as meliponic pasture, were 39 forest species

typical of both primary and secondary forest (Table 3). These species belong to

21 different families, some of which are spontaneous

and others have been introduced into the system to enrich the vegetation.

The average of plant

species present in the meliponarios was approximately

12 species ± 8, with a maximum of 24 species, found in a yard of one hectare,

while the lowest riches were found in 3 yards with a size of 2 ha and 0.5 ha.

|

Table 3. List of species, botanical families and visitation by stingless bee

species, according producers in Belterra, Pará. |

|||||

|

Popular name |

Cientific name |

Botanical Family |

Use |

Visitation by species of SBS** |

Flowering period |

|

“Tatapiririca” |

Tatapirira guianensis

Aubl. |

Anacardiaceae |

Wood Reforestation |

All |

Jun

to Sep |

|

“Cajarana” |

Cambrela canjerana |

Anacardiaceae |

Food |

Jataí |

No information |

|

“Taperebá” |

Spondias mombin

L. |

Anacardiaceae |

Food |

Trigona Jataí |

Aug

to Nov |

|

Mango |

Mangifera indica L. |

Anacardiaceae |

Food |

Canudo Jataí |

No information |

|

“Sucuuba” |

Himatanthus sucuuba (Spruce ex Mull. Arg.)

Woodson |

Apocynaeae |

Wood |

N.I |

Apr

to Jul |

|

“Marupá” |

Simarouba sp

Aubl. |

Araliaceae |

Wood |

N.I |

No information |

|

“Açaí” |

Eutherpe oleraceae

Mart. |

Arecaceae |

Food |

Jataí Canudo |

Feb

to May |

|

“Bacaba” |

Oenecarpus bacaba Mart. |

Arecaceae |

Food |

N.I |

Jun

to Oct |

|

“Pupunha” |

Bactris

gasipaes (Kunt) |

Arecaceae |

Food |

N.I |

No information |

|

“Urucum’ |

Bixa

orellana L. |

Bixaceae |

Food |

N.I |

No information |

|

“Piquiá” |

Caryocar brasiliensis (Aubl.) Pers. |

Caryocaraceae |

Wood Food |

N.I |

Aug

to Oct |

|

“Pau ferro” |

Libidibia férrea (Mart.

Ex Tul.) |

Fabaceae |

Wood |

Jataí |

No information |

|

“Cumaru” |

Dipteryx odorata

(Aubl.) Wild. |

Fabaceae |

Wood Seeds Oil |

N.I |

Feb

to Mar |

|

“Tachi preto” |

Tachigalia paniculata

Aubl. |

Fabaceae |

Buildings |

N.I |

Dec

a Feb |

|

“Tachi branco” |

Tachigalia

paraenses (Huber) Barneby |

Fabaceae |

Energy RDA* |

N.I |

Jun

to Sep |

|

“Ingazeiro” |

Inga sp |

Fabaceae |

Food |

N.I |

No information |

|

“Uchi” |

Endopleura

uchi (Huber) Cuatrec. |

Humiriaceae |

Wood Food |

N.I |

Jul to Nov |

|

“Louro” |

Laurus nobillis

L. |

Lauraceae |

No information |

N.I |

No information |

|

Avocado tree |

Persea americana |

Lauraceae |

Food |

Frisiomelita |

No information |

|

“Castanha do Pará” |

Bertholethia excelsa

Bonpl. |

Lecythidaceae |

Food |

Solitárias |

Sep

to Dec |

|

“Fava de espinho” |

Não

identificado |

Lecythidaceae |

RDA |

N.I |

No information |

|

“Muruci da mata” |

Não

identificado |

Malpighiaceae |

RDA |

N.I |

No information |

|

“Murucizeiro” |

Byrsonima

crassifólia ((L.) Rich.) |

Malpighiaceae |

Food |

N.I |

No information |

|

“Cupuaçu” |

Theobroma grandiflorum (Willd. ex

Spreng.) Schum. |

Malvaceae |

Food |

Plebeia |

No information |

|

“Canela de velho” |

Miconia albicans

(Sw.) Triana |

Melastomataceae |

RDA Medicinal |

N.I |

No information |

|

“Andiroba” |

Carapa guianensis

Aubl. |

Meliaceae |

Oil,

seeds |

N.I |

Aug

to Sep |

|

“Jaqueira” |

Artocarpus

heterophyllus Lam. |

Moraceae |

Food |

N.I |

No information |

|

Banana tree |

Musa

spp L. |

Musaceae |

Food |

N.I |

No information |

|

“Murta” |

Myrtus spp

L. |

Myrtaceae |

Medicinal |

N.I |

No information |

|

“Jambo” |

Syzygium

jambos (L.) Auston |

Myrtaceae |

Food |

N.I |

No information |

|

“Araçá” |

Psidium

cattleianum Sabine |

Myrtaceae |

Food |

N.I |

No information |

|

“Princesa da Amazônia” |

Não

identificado |

Não identificado |

No information |

All |

No information |

|

“Pau fumaça” |

Não

identificado |

Não identificado |

RDA |

All |

No information |

|

“Preciosa” |

Não

identificado |

Não identificado |

Food |

All |

No information |

|

“Limão caiano” |

Averrhoa

bilimbi L. |

Oxalidaceae |

Food |

Jataí |

No information |

|

“Limoeiro” |

Citrus limon

(L.) Burm. |

Rutaceae |

Food |

Jataí |

No information |

|

“Rambutã” |

Nephelium

lappaceum L. |

Sapindaceae |

Food |

N.I |

No information |

|

Non-identified |

Não

identificado |

Melastomataceae |

RDA |

N.I |

No information |

|

* Recovery

of Degraded Areas ** N.I – Non-Identified - there was no information about

the stingless bee species |

|||||

Table 3 shows the number of species with potential for multiple uses,

which can reduce the costs of implementing the systems for producers, since the

diversification of products with the potential to be commercialized can allow a

faster financial return. Eighteen fruit species with food use are visited by SBS

in Belterra which may indicate great potential for introduction in agroforestry

yards or other intercropped systems minimizing the costs of implementation and

maintenance. This diversity of species was also observed in the region by other

authors (SILVA; RAYOL, 2016). The number of plant species visited by SBS in the

Amazon region is high due to the coevolution of plant species with SBS, since

native bees are better adapted to the pollination of native plant species.

Barth (2004) found

that in the North Region, specifically in the State of Pará, the most commonly visited genera, species and families were Artocarpus, Bellucia, Carica, Cassia, Cocos, Leucaena, Maximiliana, Miconia, Myrtaceae, Stachytarpheta and Triplaris, Protium, besides Caesalpiniaceae, Mimosa pudica and Tapirira guianensis. Protium,

Borreria, Cassia, Cecropia, Eugenia, Miconia, Mimosa scabrella,

Tapirira

and Vismia

prevail in the city of Manaus.

Species such as “tatapiririca” and “cajueiro”,

representatives of the genera Anacardium and Tatapira,

were indicated by the producers as one of the favorites by bees, with a great

abundance of individuals in these species being observed during the flowering

period. According to Fernandes et al. (2012), the great abundance and diversity

of floral visitors in the “Tatapiririca” flowers,

occur due to the high bee potential of this species, which offers pollen and

nectar in volume and concentration of solutes attracting small insects.

The Jataí bee species,

with the highest occurrence in the studied backyards, was defined by Cortopassi-Laurino (1982) as an eclectic species in floral

visitation, while Knoll (1990) reports that the species has a

preference for the Euphorbiaceae family.

Families such as Anacardiaceae,

Caesalpiniaceae, Oxalydaceae, Rutaceae

and Sapotaceae, may have their species visited to

collect nectar and pollen (CARVALHO et al., 1995). In the interviews, the

following representatives of these families were identified, respectively: “tatapiririca”, “cajarana”, “taperebá” and mango; no representative of the

Caesalpiniaceae and Sapotaceae families and “limão caiano” were mentioned.

Maués et al. (1996) highlight that, for species such as “cupuaçu”

and “cacao”, there is a very high flowering concerning

to the number of fruits, called “Insect gratification syndrome”, an example of

mutualism and coevolution, given that, there is greater pollination intensity

of the plant and greater availability of resources for the insect, benefiting

both.

When performing melissopalinological

analyzes on species of the genus Melipona and Trigona, in forest

fragments in Manaus, Oliveira et al. (2009) found that the families most

visited by bees were: Caesalpiniaceae, Fabaceae, Mimosaceae, Myrtaceae, and the family with the highest frequency of

visits was Melastomastaceae. Likewise, in Belterra,

the interviewees also mentioned that the above mentioned

botanical families are visited by bees of the genera Melipona and Trigona.

Five species of the Fabaceae family were cited by

honey farmers as visited by the SBS, empirically characterizing the group with

the highest frequency of species. This fact was also cited by Oliveira et al.

(2009) for visitation by bees in Manaus, Amazonas.

CONCLUSIONS

Meliponiculture in the municipality

of Belterra is an activity adopted by affinity and environmental commitment of

the beekeepers, predominantly as an income supplement, exercised for a long

time, by experienced people and with honey as their main commercialized product.

The maintenance of meliponaries implies constant dedication carried out in

line with other work activities, without having continuous technical assistance

and having as main threat the deforestation and the application of pesticides,

implying the indication of agroforestry yards as the best option for the

development of the activity.

Fruit-bearing plant

species were indicated as predominant by honey farmers, characteristics of

primary and secondary forest, indicating the potential for introduction into

agroforestry yards or other intercropped systems, minimizing the costs of

implanting and maintaining meliponaries.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

To the beekeepers of Belterra for allowing us to access their

properties and for the kindness to share their experience, knowledge

and difficulties regarding the breeding of stingless bees. To the Federal

University of Western Pará and the Institute of Biodiversity and Forests for

logistical support for data sampling.

REFERENCES

BAILEY, K. Methods of social reserch. 4, ed. New York: The Free Press, 1994.

BARTH,

O. M. Melissopalynology in Brazil: a review of pollen

analysis of honeys, propolis and pollen loads of bees. Science Agricultural,

v.61, n.3, p.342-350, 2004.

BRASIL. RESOLUÇÃO CONAMA nº 346, de 16 de agosto de 2004.

Publicada no DOU nº 158, de 17 de agosto de 2004, Seção 1, página 70.

Disciplina a utilização das abelhas silvestres nativas, bem como a implantação

de meliponários.

BROWN, J. C.; OLIVEIRA, M. L. The

impact of agricultural colonization and deforestation on stingless bee (Apidae:

Meliponini) composition and richness in Rondônia,

Brazil. Apidologie, v.45, p.172-188, 2014. 10.1007/s13592-013-0236-3.

CARVALHO, C.A.L. de; MARQUES, O.M.;

SAMPAIO, H.S. de V. Abelhas (Hymenoptera, Apoidea) em Cruz das Almas-Bahia: espécies coletadas em

fruteiras. Insecta, v.4,

n.1, p.11-17, 1995.

CORDEIRO,

H. K. C.; MENEZES, C. Análise

da capacidade produtiva de própolis em diferentes espécies de abelhas sem

ferrão. XXIV CONGRESSO

BRASILEIRO DE ZOOTECNIA, 2014.

CORTOPASSI-LAURINO, M. Divisão de

recursos tróficos entre abelhas sociais, principalmente em Apis

mellifera Linn. e Trigona (Trigona) spinipes Fabricius(Apidae, Hymenoptera). 1982. 180f.

Tese (Doutorado) Instituto de

Biociências, Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, 1982.

CORTOPASSI-LAURINO, M;

IMPERATRIZ-FONSECA, V. L.; ROUBIK, D W.; DOLIN, A.; HEARD, T.; AGUILAR, I.;

VENTURIERI, V. C.; EARDLEY, C.; NOGUEIRA-NETO, P. Global meliponiculture:

challenges and opportunities. Apidologie, 37, p.

275-292, 2006.

COSTA, T. V.; FARIAS, C. A.

G.; BRANDÃO, S. C. Meliponicultura em comunidades tradicionais do Amazonas. Revista Brasileira de Agroecologia, v.7,

n.3, p.106-115, 2012.

DEEPAST.

Agricultura: Veja produção agrícola e área plantada por cidade do Brasil -

BELTERRA, PA. Disponível em: <http://www.deepask.com/goes?page=belterra/PA-Agricultura:-Confira-a-producao-agricola-e-a-area-plantada-no-seu-municipio>.

Acesso em 17 de agosto de 2020.

FARIA,

L, M. S. Aspectos gerais da Agroecologia no Brasil. Revista Agroambiental, v.6, n.2, p.101-111, 2014. http://dx.doi.org/10.18406/2316-1817v6n22014556

FERNANDES, M. M.; VENTURIERI, G. C.; JARDIM, M. A. G.

Biologia, visitantes florais e potencial melífero de Tapirira

guianensis (Anacardiaceae)

na Amazônia Oriental. Revista de Ciências Agrárias, v.55, n.3, p.167-175, 2012.

GEHRKE, R. Meliponicultura:

O estudo de caso dos criadores de abelha nativa sem ferrão do Vale do Rio

Rolante (RS) - Porto Alegre. 2010. 215f. Dissertação (Mestrado em

Desenvolvimento Rural) Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre,

2010.

KERR, W. E.; CARVALHO, G. A.; NASCIMENTO, V. A. Abelha uruçu: biologia, manejo e conservação.

Fundação Acangau. Coleção Manejo da vida silvestre,

2. Belo Horizonte: 1996. 143p.

KNOLL, F. do R. N. Abundância relativa, sazonalizada e preferências florais de Apidae

(Hymenoptera) em uma área urbana (23º 33’S; 46º

43’W). 1990. 127f. Tese (Doutorado) Instituto de Biociências, Universidade de

São Paulo, São Paulo, 1990.

LIMA, L. N. NOGUEIRA, E. de. S. Produção e uso dos

recursos melíferos por meliponicultores da região de Cícero Dantas, BA. Gaia Scientia, v.11, n.3, p.73-82, 2017. 10.22478/ufpb.1981-1268.2017v11n3.29111

LOPES, M; FERREIRA; SANTOS, J. B. G.

dos. Abelhas sem-ferrão: a biodiversidade invisível. Agriculturas, v.2, n.4, p.7-9, 2005.

MAGALHÃES, T. L de; VENTURIERI, G. C. Aspectos

econômicos da criação de abelhas indígenas sem ferrão (Apidae:

Meliponini) no Nordeste paraense. Embrapa Amazônia Oriental-Documentos

(INFOTECA-E), 2010.

MAIA-SILVA, C. et al. Stingless bees (Melipona subnitida) adjust brood production rather than foraging

activity in response to changes in pollen stores. Journal of Comparative Physiology A, v. 202, p. 723-732, 2016.

MAUÉS, M. M.; VENTURIERI, G. C.; DE SOUZA, L. A.;

NAKAMURA, J. Identificação e técnicas

de criação de polinizadores de espécies vegetais de importância econômica no

estado do Pará. EMBRAPA. Centro de Pesquisa Agroflorestal da Amazônia

Oriental (Belém,PA). Geração

de tecnologia agroindustrial para o desenvolvido do trópico úmido. Belém:

EMBRAPA - CPATU / JICA. p.305, 1996.

MEIRELES, A. M.; TAVARES, F.

B.; LOPES, E. L. N.; CORDEIRO, Y. E. M. Aspectos econômicos, sociais e

ambientais inerentes a atividade de meliponicultura

no baixo Tocantins, estado do Pará”, Revista Observatorio

de la Economía Latinoamericana, 2018.

MELLO, F. P.; SOUZA, B, A;

LOPES, M. T. R. Instalação e manejo de meliponário -

Teresina: Embrapa Meio-Norte, p. 26, 2010.

OLIVEIRA,

F. P. M.; ABSY, M. L.; MIRANDA, I. S. Recurso polínico coletado por abelhas sem ferrão (Apidae,

Meliponinae) em um fragmento de floresta na região de

Manaus – Amazonas. Acta Amazonica. v.39, n.3,

p.505–518, 2009.

PEREIRA, F. M. Instalação e manejo de meliponários. Embrapa Meio-Norte, 2010.

PINHEIRO, J.N.; FREITAS, B.M.

Efeitos letais dos pesticidas agrícolas sobre polinizadores. Oecologia Australis.

v. 14, n.1, p, 266-281, 2010.

PINTO, G. S. Diagnóstico da meliponicultura em Belterra, PA e

caracterização física, química e microbiológica de méis de Scaptotrigona sp. (canudo-amarela). Belem,

Tese, 100 p. 2012.

RAYOL, Breno Pinto; MAIA, Raimundo

Tarcísio Feitosa. Potencial da inserção de abelhas em sistemas agroflorestais

no oeste do estado do Pará, Brasil. Revista Brasileira de Agroecologia, v.8, n.3, p.101-108, 2013.

SANTOS, A. B. Abelhas nativas: polinizadores em

declínio. Natureza on line v.8, n.3, p.103- 106, 2010.

SILVA, F. L. da;

OLIVEIRA, F. de A.; AMIN, M. M.; BELTRÃO, N. E. S.; ANDRADE, V. M. S. Dimensões do uso e cobertura de terra nas

mesorregiões do estado do Pará. Espacios, v.37, n.05,

p.5, 2016.

SILVA, J. C. N.; RAYOL, B. P.

Diversidade de árvores nos quintais urbanos do município de Belterra,

Oeste do Pará. Cadernos de

Agroecologia, v. 10, n. 3, 2016.

SILVA, M. D.; MONTEIRO, D.; SILVA, M.; OLIVEIRA, R. B.;

QUEIROZ, M. V. M; SANTOS, J. F. Padrão de distribuição espacial de ninhos de Meliponini (Hymenoptera: Apidae) em função da disponibilidade de recursos para

nidificação em um fragmento de Mata Atlântica em Salvador, Bahia, Brasil.

Magistra, Cruz das Almas-BA, v.24, p.91-98, 2012.

SILVA, W. P.; PAZ, J. R. L. Abelhas sem

ferrão: muito mais do que uma importância econômica. Natureza on line, v.10, n.3, p.146-152, 2012.

SIQUEIRA, A. L. Estudo da ação

antibacteriana do extrato hidroalcoólico de própolis

vermelha sobre Enterococcus faecalis. Revista de Odontologia da UNESP, v.43,

n.6, p.359-366, 2014.

VENTURIERI,

A; COELHO, A. de S.; THALES, M. C.; BACELAR, M. D. R. Análise da expansão da

agricultura de grãos na região de Santarém e Belterra,

Oeste do estado do Pará. Anais XIII Simpósio Brasileiro de Sensoriamento

Remoto, Florianópolis, Brasil, INPE, p. 7003-7010, 2007.

VENTURIERI, G. C., The impacto

f forest exploitation on Amazonian stinglees bees

(Apidae, Meliponini). Genetics and Molecular Research v8: p.684-689,

2009.

WINFREE, R.; AGUILAR, R.;

VAZQUEZ, D. P.; LEBUHN G.; AIZEN, M. A. A meta-analysis of bees' responses to

anthropogenic disturbance. Ecology, v.90, n.8, p.2068-2076, 2009.